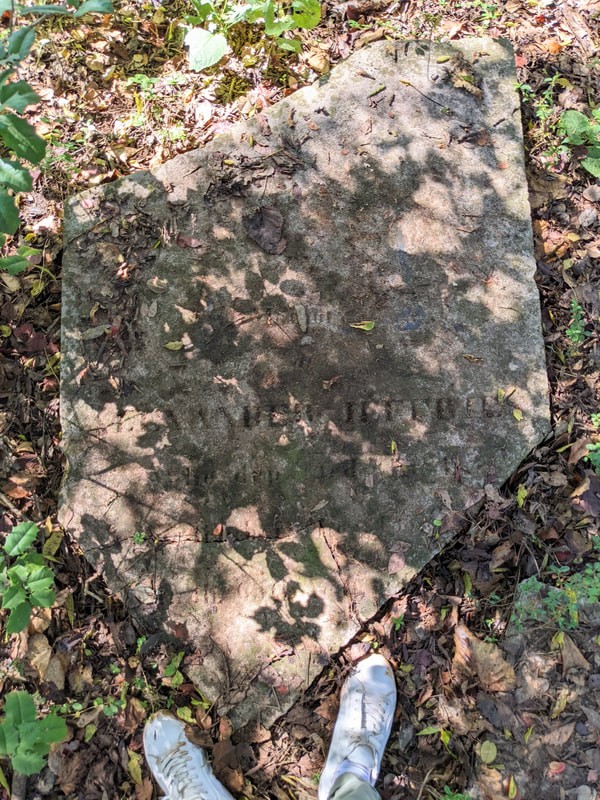

Alexander Jeffries (1773-1838); his first wife Frances Jeffries (d. 1824); Mary Elizabeth Jeffries (1837-1844), the seven-year-old daughter of Alexander and his second wife; and the empty grave of his father-in-law Adam Dale (1768-1851), veteran of the War of 1812. Alexander Jeffries was a cotton planter in antebellum Alabama, the owner of a large estate and dozens of enslaved people to work it. When he died in 1838, he left his land and property to his second wife and their two children, naming his widow -- born Elizabeth Evans Dale -- as the executrix of his estate. Elizabeth is known to history as Mrs. Gibbons Flanagan Jeffries High Brown Routt. By the age of 56, she'd been wed and widowed six times -- a love life that's made her the subject of whispers and rumors of murder since 1838, when Alexander Jeffries died and his son Richard accused his stepmother of poisoning him.

0 Comments

In 1851, Sarah Townsend lost two of her children. Eighteen-month-old Martha died on December 11th and four-year-old Parkes followed just two weeks later, the day after what must have been a grave and solemn Christmas. Three years later, her six-year-old namesake Sarah died as well -- also in December. Sarah and her husband John buried their children side by side in the tree-shaded Townsend family cemetery in Hazel Green, Alabama. Today, low white pillars carved with stone wreaths still mark their graves. Child and infant deaths in the 19th century were extraordinarily high. In 1850, the mortality rate for American children under the age of five was approximately 399 deaths per 1,000 births. Or in other words: for every 1,000 babies born that year, nearly 40% would die before the age of five.[1] Respiratory illnesses like influenza and pneumonia caused 22% of child deaths under the age of 14 in the year 1900; gastrointestinal diseases like dysentery and cholera accounted for another 20%.[2] Fifty years earlier, those numbers would have been even higher. Martha, Parkes, and little Sarah may have died from something as seemingly insignificant as a winter cold.

Historians often talk about "buried secrets" and "digging up the past," but -- unlike archaeologists -- for us, it's usually a metaphor. Sometimes, however, history really is buried. In honor of spooky season, I'll be sharing stories this month from a few of the cemeteries I've visited over the course of my research, and the insights I gained there that I couldn't have learned from the archive. Note: No graves were disturbed in the making of this post. North of Huntsville, Alabama, in the tiny community of Hazel Green, a low stone wall marks the gravesite of two brothers: Samuel and Edmund Townsend. Located directly adjacent to a cornfield, the green, grassy cemetery sits on land the Townsend brothers once owned. Samuel and Edmund were wealthy white cotton planters of the antebellum era, multi-millionaires by today's standards, with thousands of acres of farmland, herds of hogs and cattle, stands of beehives for honey, and a big house shaded by fruiting pecan trees. They were the aristocrats of the pre-Civil War South, and their lifestyle was only possible because they kept hundreds of enslaved people in bondage on their vast plantations.

Lizzy arrived in Alabama the year the stars fell. She was ten or eleven--she couldn’t say for sure--but for the rest of her life she would remember that night in 1833 when the world seemed to be ending. Around midnight on November 13, shooting stars began to fill the skies east of the Rocky Mountains, with Alabamians receiving the most spectacular view. Flashes of light and booming sounds woke people and drew them outside as meteors passed through the Earth’s atmosphere, dozens per second and hundreds per minute, according to some estimates. It was "as if the planets and constellations were falling from their places," one newspaper reported the next day. As the shower continued unabated for hours, witnesses started to wonder whether this was the long-awaited second coming of Christ. "And the stars of the heaven fell unto the earth," the book of Revelation reads, "for the great day of his wrath is come, and who shall be able to stand?" Terrified onlookers cried or prayed or simply stared in wonder. Up north in Illinois, a young man named Lincoln heard his innkeeper shouting "Arise, Abraham, the day of judgment has come!" For a century after, Alabama residents would mark time by the year the stars fell, the dividing line for local and personal histories. It was the dividing line for Lizzy too, a night the sky seemed to reflect what must certainly have felt like the end of her world: the year she was forced to leave her home in Virginia, sent west on a 700-mile trek to Alabama, and sold to a man named Edmund Townsend.

|

Blog byAward-winning author and historian of slavery R. Isabela Morales Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed