|

Happy to announce that the Princeton Alumni Weekly is running an excerpt from Happy Dreams of Liberty in their Featured Authors section (the dream of any Princeton grad). You can check it out here.

0 Comments

If you have a long road trip or plane ride coming up this holiday season, do I have good news for you: Happy Dreams of Liberty will be released as an audiobook on December 26, narrated by Allyson Johnson. You can find it on Audible.com, Spotify, iTunes, Google Play, and other online retailers.

Allyson Johnson has narrated titles by groundbreaking historians such as Annette Gordon-Reed, Nell Irvin Painter, and Tiya Miles (along with many other distinguished authors -- including Neil deGrasse Tyson), so it's an honor and a pleasure to hear her read Happy Dreams of Liberty. So that's 9 hours and 20 minutes of my travel time covered...

The Frederick Douglass Prize is awarded by Yale University's Gilder Lehrman Center and recognizes the best book written on slavery, resistance, or abolition in the last year. From the press release: Gilder Lehrman Center director David W. Blight commended the two books for the “breadth and depth of their scholarship and sensitive treatment of human-centered struggles for emancipation.” Jury chair Kerry Ward added that, in combination, the “compelling writing” of the winning books helps readers understand “the diversity of the experiences of slavery in different times and places,” with people centered at the heart of these stories. Simon Newman's book is Freedom Seekers: Escaping from Slavery in Restoration London, and is available from the University of Chicago Press. Scars on the Land: An Environmental History of Slavery in the American South, by Dr. David Silkenat of the University of Edinburgh, was also shortlisted for this year's prize, and is available from Oxford University Press.

I am delighted to announce that Happy Dreams of Liberty has been awarded the William Nelson Cromwell Foundation Book Prize from the American Society for Legal History. I've always conceptualized this book as a family history first and foremost, so to be counted among legal historians is an honor.

Throughout the research and writing process for this book, I faced the same challenges that any historian of slavery faces: the difficulty of finding the voices and experiences of enslaved people in the archive. In this case, I used a legal archive. It's a family history told through wills, inventories, financial statements, and depositions. (Word to the wise: depositions are where you find all the juicy gossip.) I tried to use these legal sources as creatively as I could to reconstruct the lives of the Townsend family in slavery and the ways that the law shaped the possibilities for their lives in freedom. This week, The Daily Princetonian (Princeton University's campus newspaper) published an article recognizing the 10-year anniversary of The Princeton & Slavery Project -- which means it's my 10-year work anniversary too. I've been involved with the project since it was founded as a single undergraduate research seminar taught by Princeton history professor Martha Sandweiss, first as a researcher and writer and now the project's editor and project manager.

From that first course in 2013, the project has expanded into a major digital history initiative, with all of our findings fully accessible to the public on our website. There, you'll find a digital archive of 400+ primary sources and more than 100 interpretive essays investigating Princeton University's historical links to the institution of slavery.

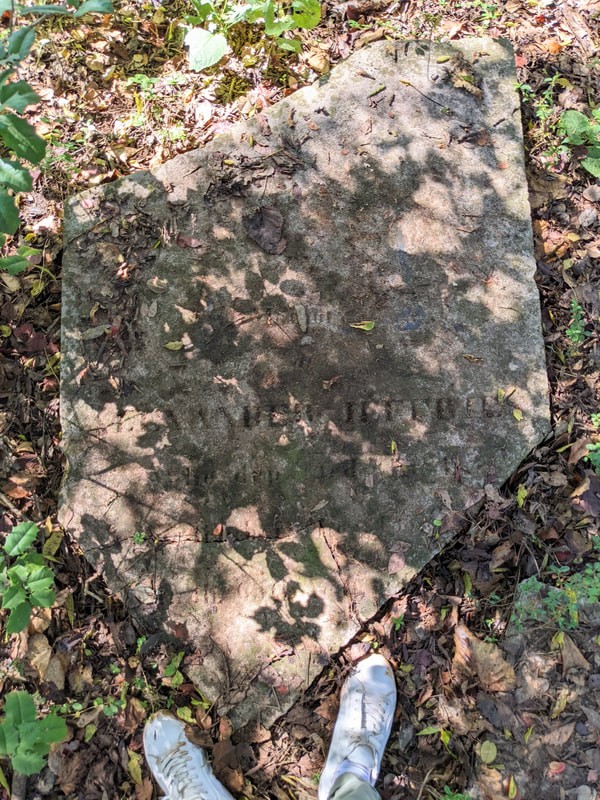

Alexander Jeffries (1773-1838); his first wife Frances Jeffries (d. 1824); Mary Elizabeth Jeffries (1837-1844), the seven-year-old daughter of Alexander and his second wife; and the empty grave of his father-in-law Adam Dale (1768-1851), veteran of the War of 1812. Alexander Jeffries was a cotton planter in antebellum Alabama, the owner of a large estate and dozens of enslaved people to work it. When he died in 1838, he left his land and property to his second wife and their two children, naming his widow -- born Elizabeth Evans Dale -- as the executrix of his estate. Elizabeth is known to history as Mrs. Gibbons Flanagan Jeffries High Brown Routt. By the age of 56, she'd been wed and widowed six times -- a love life that's made her the subject of whispers and rumors of murder since 1838, when Alexander Jeffries died and his son Richard accused his stepmother of poisoning him.

In 1851, Sarah Townsend lost two of her children. Eighteen-month-old Martha died on December 11th and four-year-old Parkes followed just two weeks later, the day after what must have been a grave and solemn Christmas. Three years later, her six-year-old namesake Sarah died as well -- also in December. Sarah and her husband John buried their children side by side in the tree-shaded Townsend family cemetery in Hazel Green, Alabama. Today, low white pillars carved with stone wreaths still mark their graves. Child and infant deaths in the 19th century were extraordinarily high. In 1850, the mortality rate for American children under the age of five was approximately 399 deaths per 1,000 births. Or in other words: for every 1,000 babies born that year, nearly 40% would die before the age of five.[1] Respiratory illnesses like influenza and pneumonia caused 22% of child deaths under the age of 14 in the year 1900; gastrointestinal diseases like dysentery and cholera accounted for another 20%.[2] Fifty years earlier, those numbers would have been even higher. Martha, Parkes, and little Sarah may have died from something as seemingly insignificant as a winter cold.

Historians often talk about "buried secrets" and "digging up the past," but -- unlike archaeologists -- for us, it's usually a metaphor. Sometimes, however, history really is buried. In honor of spooky season, I'll be sharing stories this month from a few of the cemeteries I've visited over the course of my research, and the insights I gained there that I couldn't have learned from the archive. Note: No graves were disturbed in the making of this post. North of Huntsville, Alabama, in the tiny community of Hazel Green, a low stone wall marks the gravesite of two brothers: Samuel and Edmund Townsend. Located directly adjacent to a cornfield, the green, grassy cemetery sits on land the Townsend brothers once owned. Samuel and Edmund were wealthy white cotton planters of the antebellum era, multi-millionaires by today's standards, with thousands of acres of farmland, herds of hogs and cattle, stands of beehives for honey, and a big house shaded by fruiting pecan trees. They were the aristocrats of the pre-Civil War South, and their lifestyle was only possible because they kept hundreds of enslaved people in bondage on their vast plantations.

Lizzy arrived in Alabama the year the stars fell. She was ten or eleven--she couldn’t say for sure--but for the rest of her life she would remember that night in 1833 when the world seemed to be ending. Around midnight on November 13, shooting stars began to fill the skies east of the Rocky Mountains, with Alabamians receiving the most spectacular view. Flashes of light and booming sounds woke people and drew them outside as meteors passed through the Earth’s atmosphere, dozens per second and hundreds per minute, according to some estimates. It was "as if the planets and constellations were falling from their places," one newspaper reported the next day. As the shower continued unabated for hours, witnesses started to wonder whether this was the long-awaited second coming of Christ. "And the stars of the heaven fell unto the earth," the book of Revelation reads, "for the great day of his wrath is come, and who shall be able to stand?" Terrified onlookers cried or prayed or simply stared in wonder. Up north in Illinois, a young man named Lincoln heard his innkeeper shouting "Arise, Abraham, the day of judgment has come!" For a century after, Alabama residents would mark time by the year the stars fell, the dividing line for local and personal histories. It was the dividing line for Lizzy too, a night the sky seemed to reflect what must certainly have felt like the end of her world: the year she was forced to leave her home in Virginia, sent west on a 700-mile trek to Alabama, and sold to a man named Edmund Townsend.

Next week, I will be providing expert public comment at the first session of the New Jersey Reparations Council. This is a virtual meeting, open to the public, and anyone can watch on the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice's YouTube channel next Tuesday, September 16, at 6:30 PM (ET). I've worked on The Princeton & Slavery Project since 2013, so I've spent the last decade learning and writing about the history of slavery in the North -- but it wasn't something I got much of in high school or college. Slavery is often portrayed (in popular culture and the classroom) as a strictly southern institution. That's far from the case, and it's why we need informed conversations like the upcoming NJ Reparations Council meeting. Whether you plan to attend the session or not, I highly recommend The Price of Silence: The Forgotten Story of New Jersey's Enslaved People to anyone interested in learning more about slavery in the "free" states. I'm fortunate to have contributed to the film, and am delighted that it was recognized with a NY Emmy nomination this year. The full 30-minute documentary is free to watch on YouTube or the PBS website. |

Blog byAward-winning author and historian of slavery R. Isabela Morales Archives

December 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed